When Wiltonians think about their town’s Native American connections, several things probably come to mind. First there are names like Pimpewaug, Indian Hill, and Chicken Street (namesake of Chi-ken Warrups, who sold land to the founder of Redding). Then there is the rock shelter in Rock House Woods (Town Forest). Some may have seen F. Clerc Ogden’s collection of stone projectiles at the Wilton Historical Society. Others might think of the Wilton Warriors, whose original association with an “Indian warrior” has proven difficult to shake, despite official re-branding as Trojan warriors in 1973.

When Wiltonians think about their town’s Native American connections, several things probably come to mind. First there are names like Pimpewaug, Indian Hill, and Chicken Street (namesake of Chi-ken Warrups, who sold land to the founder of Redding). Then there is the rock shelter in Rock House Woods (Town Forest). Some may have seen F. Clerc Ogden’s collection of stone projectiles at the Wilton Historical Society. Others might think of the Wilton Warriors, whose original association with an “Indian warrior” has proven difficult to shake, despite official re-branding as Trojan warriors in 1973.

The reality is that Wilton belonged to Native Americans. The oldest traces lie under the community gardens in Allen’s Meadows, along the ancient Berkshire Path, now Route 7. Excavated by Ernest A. Wiegand, professor of archaeology at Norwalk Community College, this Paleoindian site has produced numerous stone and ceramic artifacts, including a 12,000-year-old Crowfield point. While Wiegand cautions that the site’s precise nature cannot be determined, he suspects it was a temporary encampment, and – based on the prevalence of stone scrapers – conceivably used to exploit seasonal movements of caribou through the Norwalk River Valley.

Relatively intact sites like Allen’s Meadows are irreplaceable and increasingly rare. Development has already destroyed several in Wilton, though some were first excavated so their lessons at least are preserved. One was Tumbleturd Hill (its real name, I promise) in an ASML parking lot. Like Allen’s Meadows, it is on the ancient Berkshire Path / Route 7 corridor. According to Wiegand, Tumbleturd’s steep sides provided a natural windbreak and overhanging rock shelter for Archaic and early Woodland Native Americans between 5000 BCE and 1200 CE. Charred hickory nuts indicate the site was used in September and October. Other finds include deer bones, stone knives and scrapers, and pottery shards.

Relatively intact sites like Allen’s Meadows are irreplaceable and increasingly rare. Development has already destroyed several in Wilton, though some were first excavated so their lessons at least are preserved. One was Tumbleturd Hill (its real name, I promise) in an ASML parking lot. Like Allen’s Meadows, it is on the ancient Berkshire Path / Route 7 corridor. According to Wiegand, Tumbleturd’s steep sides provided a natural windbreak and overhanging rock shelter for Archaic and early Woodland Native Americans between 5000 BCE and 1200 CE. Charred hickory nuts indicate the site was used in September and October. Other finds include deer bones, stone knives and scrapers, and pottery shards.

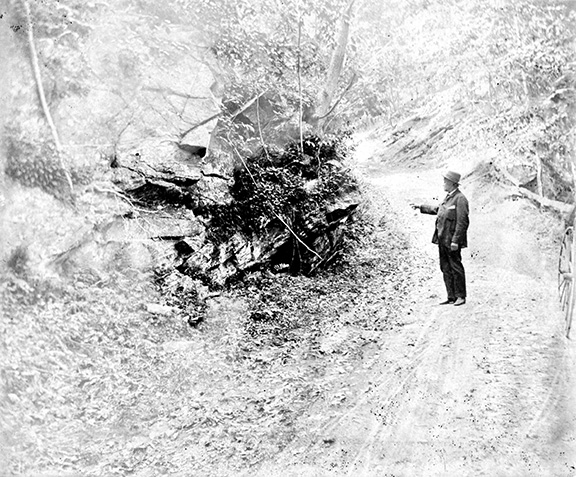

Another site is the Town Forest’s rock shelter. Bernard W. Powell excavated here in 1972. Although frequently vandalized (it was tagged with graffiti when Powell first saw it), this site has yielded evidence of Woodland and post-contact (after the arrival of Europeans) use. Powell found arrowheads, pottery, deer bones, and shellfish remains, alongside musket balls and a Spanish coin dropped by some passing Native American or Englishman in colonial times.

Whose land is this?

Whose land is this?

By the time European settlers arrived, the Siwanoys occupied Norwalk and Wilton. Colonists negotiated in 1640 and 1641 with the Siwanoy sachem or chief, Mahackemo, and others for the territory between the Saugatuck and Five Mile rivers, beginning at the coast and stretching inland twelve miles. This territory included the seasonal village of Norwalke or Norwake, after which the English settlers named their own settlement.

While colonists may have believed they were purchasing land outright, the Siwanoys viewed the deal differently: they were granting the right to use their territory. Population pressure on land was at a historic low. Native Americans were decimated by European plagues beginning in the 1610s. As a result there were fewer mouths to feed and less land needed to feed them. At the same time labor was scarce, making the novel devices offered by the English – metal tools in particular – more valuable. And so, Mahackemo accepted eighteen fathoms (36 yards) wampum, ten fathoms tobacco, thirteen hatchets, hoes, and knives, sixteen mirrors, twelve pipes, ten jaw harps, drills, scissors, and needles, six coats, and three kettles.

It seems not just the Siwanoys but the early settlers, too, shared this interpretation, despite boilerplate language that “noe Indian or other shall challenge or claim any ground within the sayed Rivers or limits.” In actual practice, Native Americans continued to live in areas of Norwalk that initially remained unsettled by the new residents. Because the number of whites was small and all lived within a mile of the newly established Meeting House, Native American usage of the lands they “sold” changed little in the 1640s and 1650s.

As late as 1669, laws in the Norwalk Town Records show that English proprietors were renting out their personal allotments to Native Americans for planting. There are also references to the “Indian Field,” areas designated for Siwanoy use. In 1671, the Norwalk selectmen reserved Wilton’s Chestnut Hill “for a field for the Indians,” showing that thirty years after Mahackemo’s sale, Native Americans were still living within Norwalk’s boundaries. This same record hints at the settlers’ incipient attempts, as their demands for land intensified, to contain Native Americans to more restricted territories.

By 1726, most Native Americans remaining in Norwalk and the newly formed Wilton Parish were either indentured or enslaved. In 1744, Alexander Hamilton noted that Norwalk’s “servants [were] chiefly bound or indentured Indians” rather than enslaved Black people. Among these Native Americans were Will and Elizabeth; their “master” was John Belden II, a major property owner in what is now Georgetown. In 1750, one Stephen Rogers accused them of breaking into his store, stealing liquor, and spilling thirty-six gallons of rum. Belden testified that Will and Elizabeth had been in his house all night. Despite Will’s instinct to confess – convinced that no one would believe a pair of enslaved Indians – they pled not guilty. Belden’s testimony and evidence that an indentured white woman had committed the crime (and pinned it on Will and Elizabeth) led to their exoneration.

Honoring the past

Honoring the past

By 1774, the state census identified only nine Native Americans in Norwalk and Wilton. Unknown numbers of the 136 Black people recorded that year, however, surely had mixed African and Native American ancestry. Among these possibly, was Prince Tonquin, son of an enslaved Black woman and Bill Tonquin, an enslaved Native American. Fathering a large family in Wilton, Prince ensured his legacy of mixed Native American and African American ethnicity and culture would continue in town for at least another generation. His last known descendant died in 1893 and is buried at St. Matthew’s Cemetery.

Like so many aspects of Wilton’s Native American history, the grave of Prince’s last heir is unmarked and too easily overlooked. Yet, remains of the town’s indigenous past are nearly ubiquitous. While we must look for and learn about local sites, we shouldn’t jump in to disturb them any more than we would desecrate a grave. Honoring the relics of those people who came before us and whose land our forefathers took is the least we can do.