In 1653 in Fairfield, CT, Goodwife Knapp was accused of witchcraft. Details of her case are scarce, and even her first name has been lost to history. However, historians know that after being accused by Roger Ludlow, Fairfield’s founder, she refused to accuse the wife of one of Ludlow’s rivals of witchcraft.

She was convicted and executed by hanging that same year.

Ludlow was and is celebrated in Fairfield and both a middle school and high school in town bear his name, while Knapp was largely forgotten except by her descendants and local history enthusiasts, until recently.

A verdict years in the making

A verdict years in the making

Three-hundred and seventy years after Knapp’s execution, on March 1of this year, her great to the 10th power granddaughter, Beverly Kahn, testified before the Connecticut legislature’s Judiciary Committee in support of a resolution to officially pardon Knapp and others accused of witchcraft in Colonial Connecticut.

“Please do the right thing,” Kahn said. “Exonerate Goody Knapp and all the others – and send a message to the citizens of Connecticut today that accusation, hatred, and killing are wrong.”

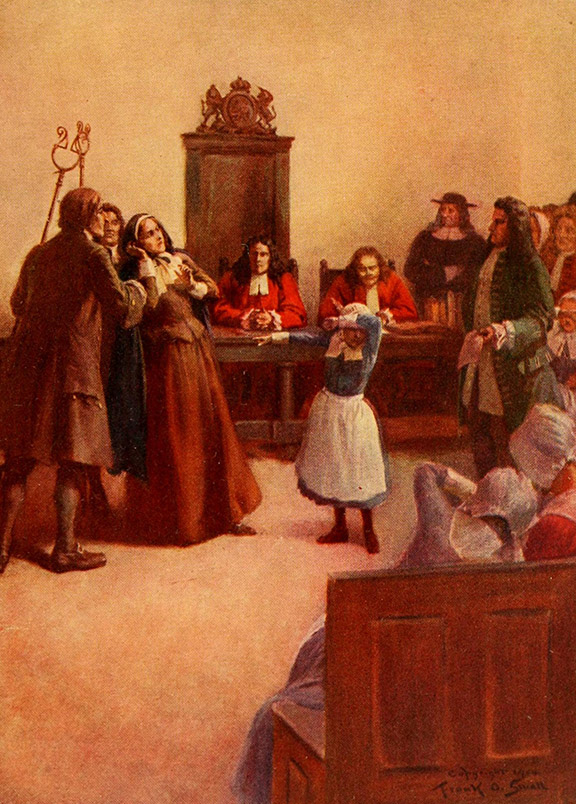

Though lesser known than the Salem witch trials, Connecticut’s witch trials were often equally as intense. They began in 1647 and continued until 1663. During that time at least 34 people were accused of witchcraft, 12 were convicted and 11 of those were executed.

In Fairfield County, Goody Bassett was tried and hanged in Stratford in 1651 (two years prior to Knapp’s execution). During the Stamford-Fairfield Witch-Hunt of 1692 six people were accused of witchcraft but only one was convicted and none were executed.

The names of all known Connecticut witch hunt victims were officially cleared in May 2023 when the Connecticut legislature voted in favor of a resolution to pardon them. The resolution passed thanks to a grassroots effort of descendants of the victims, like Kahn, as well as local historians.

Misogynistic Malice

Though there were Connecticut men who were accused of witchcraft, including two men who were executed, women were much more often the victims of witch hunts. “Misogyny is at the heart of witch trial accusations even though both men and women were accused,” says Beth Caruso, co-founder of the Connecticut Witch Trial Exoneration Project, as well as an author and historian. “The majority of those accused, indicted and also killed were women and most of the men accused were connected to women who were accused.”

Even when accused of witchcraft men and women received different treatment. “Only women had to endure the humiliating experience of being searched for ‘witch’s teats’ or ‘marks of the devil’ after being stripped naked,” Caruso says. Mary Louise Bingham, another co-founder of the Connecticut Witch Trial Exoneration Project, adds that misogyny can also be seen in the belief of the time that mothers would pass the tradition of witchcraft onto their daughters, but fathers would not pass it on.

In the Thou Shalt Not Suffer: The Witch Trial Podcast, Connecticut Witch Trial Exoneration Project co-founders Joshua Hutchinson and Sarah Jack discuss how some people who accused witches were so terrified of those they thought were witches they would experience physical symptoms, like sweating or heart rate spikes after an encounter with them. These placebo-induced symptoms were seen as proof of malignant supernatural forces at play.

In the Thou Shalt Not Suffer: The Witch Trial Podcast, Connecticut Witch Trial Exoneration Project co-founders Joshua Hutchinson and Sarah Jack discuss how some people who accused witches were so terrified of those they thought were witches they would experience physical symptoms, like sweating or heart rate spikes after an encounter with them. These placebo-induced symptoms were seen as proof of malignant supernatural forces at play.

However, there were voices of reason in this time. John Winthrop Jr., the future governor of the Connecticut colony and a noted alchemist, realized that those accused in Connecticut were not engaged in the practice of witchcraft and witch accusations became less common thanks to his influence.

In recent years the stories of Connecticut’s accused witches have gotten more attention in part due to exoneration efforts. A memorial to Goodwife Knapp was unveiled in 2019 in the Black Rock area in Bridgeport. The Stratford Historical Society remembered Goodwife Bassett with a ball in her honor and Stratford’s mayor declared May 15 to be Goody Bassett Day.

Connecticut’s witchcraft exoneration advocates hope this awareness will help discourage discrimination and the very literal witch hunts that still occur today — globally more than 1,000 people are still accused of witchcraft each year.

Learn from the Past – Hope for the Future

Learn from the Past – Hope for the Future

Bingham says these ongoing efforts made what Connecticut did by pardoning its witch accusation victims even more important.

“As we speak, people are being killed on a daily basis as a part of witch hunts,” she says. “The people that are advocating for those victims and their families were looking at Connecticut to see how Connecticut would do.”

As for Kahn, she also hopes the story of the persecution her ancestor and others suffered can help inspire a better world.

“America is going through such conflict and cultural squabbles and demonizing people who are different today with the rise of extreme hate groups and all the rest,” Kahn says. “Perhaps if we look at the history of early America and early Fairfield that will teach us that we can be better, that we shouldn’t do this.”