Women today regularly worry how others see them. Instagram filters keep us looking youthful, posts showing healthy, delicious meals make others envy our work-life balances, and spandex shapewear maintains our appearances. But what about women a hundred and fifty years ago?

Women today regularly worry how others see them. Instagram filters keep us looking youthful, posts showing healthy, delicious meals make others envy our work-life balances, and spandex shapewear maintains our appearances. But what about women a hundred and fifty years ago?

Wilton women in the late 1800s wanted to seem respectable. A lot hinged on a good reputation; “improper” behavior could ruin everything from a young woman’s marriage prospects to an elderly widow’s financial security. Rather than face the perils of womanhood, some girls did their best to hold onto childhood. Others had no choice but to face society’s judgements head-on.

A practitioner of the former tactic was Agnes “Aggie” Fitch (1854-1942) of Wilton center. Several photographs of Aggie and a scrapbook she kept from the 1870s onward have survived.

Aggie’s earliest known photo is a “coming out” portrait of a young woman just entering adulthood and eligible for courtship. Her cheeks are tinted pink to simulate a healthy glow, her dress is dark, practical, and high-necked, and her jewelry signals family wealth, pride in her appearance, concern for punctuality, good stewardship of her possessions (note the watch chain), and the depth of her Christian faith. All of this marks Aggie as well-suited to be a successful mid-Victorian wife and mother. Unlike men’s portraits from this period, however, Aggie doesn’t hold a book or anything hinting at extensive education or profession. She would have shared this one-of-a-kind daguerreotype, a photograph printed on a piece of copper used in the 1800’s, with family, friends, and prospective suitors.

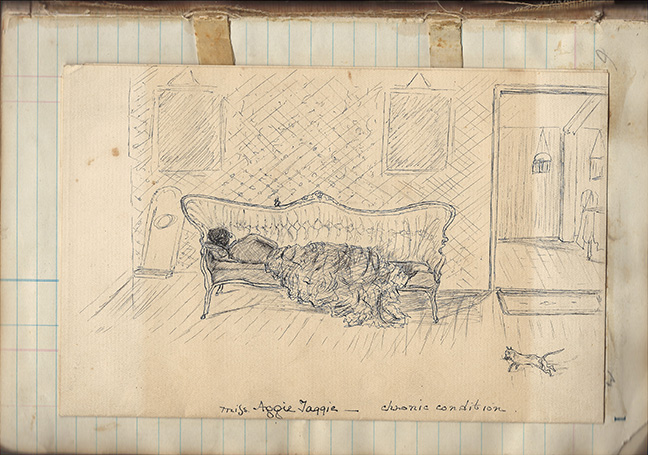

An anonymous drawing in Aggie’s scrapbook, captioned “Miss Aggie Taggie – chronic condition,” however, provides a different perspective. Unusually, it shows Aggie laying down on a couch, facing away from the artist. This view is extremely intimate for the era, surely drawn by a close friend or family member. The humorous title pokes fun at Aggie for what might have been a persistent desire to hide away at home, safe from society’s expectations. A cat scampers across the room, hinting that slumber will soon be (pleasantly) interrupted and emphasizes Aggie’s apparent childishness and refusal to act her age. Here she is, dressed as a grown woman presumably ready for marriage, yet turning away from the world and lolling about, moments away from playing with her favorite pet.

The contents of Aggie’s scrapbook reinforce this conflicting image of a virtuous young woman stubbornly holding onto childhood. Alongside notices from a Ladies Sewing Society and family news are humorous clippings about cats and a poem Aggie wrote for a friend, “Maiden that read’st this simple rhyme / Enjoy thy youth, it will not stay.”

The contents of Aggie’s scrapbook reinforce this conflicting image of a virtuous young woman stubbornly holding onto childhood. Alongside notices from a Ladies Sewing Society and family news are humorous clippings about cats and a poem Aggie wrote for a friend, “Maiden that read’st this simple rhyme / Enjoy thy youth, it will not stay.”

Ultimately, Aggie did what society expected – though she took her time about it. She married as an “old maid” of 32, had children, remained devoted to her family, and kept up with her sewing.

Fighting for her due support

Another Wilton resident of the time adopted far more direct tactics: Susan Jackson Dulliman (born c. 1820) of Sharp Hill. As a Black woman and a poor Civil War widow, Susan faced additional pressures and prejudices beyond her gender.

No pictures of Susan have survived – all that remains are scattered references to her children in the books of St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church, records of her work sewing shirts in Cannondale, census returns, and a reference to part of a house she and her husband Henry once rented from Samuel F. Lambert. Besides these scraps, more insight comes from Susan’s pension file.

After Henry died at his army camp in 1864, Susan applied for a soldier’s widow’s pension. To qualify she first had to prove her marriage was legitimate. This was tricky as Susan was semi-literate and her last name was spelled inconsistently on different records. Government agents took a dim view of this, but eventually she proved her marriage – and identity – to their satisfaction.

To receive support for two underage children (there were seven total), Susan next had to establish exact birth dates. Black births were irregularly recorded in Wilton’s church registers, and several of Susan’s babies were among those missing. While she and Henry had recorded their children in their family bible, Susan had to rely on something the courts found more persuasive: the testimony of “respectable” white Wiltonians, Dr. David Willard, midwife Laura Stewart, and neighbor Emmeline Fairchild. All attended Susan’s births, but it was Willard’s patient registers that got Susan her pension.

Thirty years later, Special Examiner A. C. Ridgeway, Bureau of Pensions, arrived in Bridgeport, where Susan had moved, to investigate rumors that she was living “in open and notorious adulterous cohabitation” with her boarder, George Holmes. Such “cohabitation” would put her in violation of an 1882 Act of Congress. Her right to continued support depended on an official evaluation of her chastity.

In the late 1800s, widows were morally suspect. Unlike wives and unwed daughters, no man directly controlled them. Additionally, racist norms insisted that Blacks were sexually licentious and dishonest. Certainly, Ridgeway and his superiors assumed Susan’s relationship with George had to be sexual – and that she was definitely lying about it.

According to Susan’s notarized testimony, Ridgeway bullied her into falsely confessing that she had had “connection” with George and was essentially his wife. She pleaded, “I was so embarrassed and flustered by [Ridgeway’s] manner and language that I was unable to understand what I had sworn to.” Unlike in Wilton, Susan found no “respectable” white allies to testify on her behalf. The government revoked her pension. Susan died sometime later and is buried at St. Matthew’s Cemetery in Wilton.

It is infuriating to read about Susan’s experiences and realize that Aggie Fitch – despite her relative privilege and its insulating power – might have suffered, too, had anything happened to question her reputation. It helps to remember that even though Susan ultimately lost her pension, she fought hard and had Wilton allies. And although Aggie waged a quieter war, she maintained her independence far longer than most. Women like these, and the many generations that followed, are the reason we have so many more freedoms today – even as additional battles remain to be won. •