Farms feed the body, but an 18th Century spread on the Ridgefield-Wilton line has instead been nurturing mind and soul for a century and a half. Today’s Weir Farm National Historical Park has been home to five notable artists, starting with a man who bought the place with a painting.

Julian Alden Weir had art in his blood. Born in 1852, son of an artist who taught at West Point, he studied at the National Academy of Design and, in 1873, went to Paris where he began to embrace plein air painting — working outdoors amid nature. At the time, however, he was disenchanted with Impressionism, considering it “worse than the Chamber of Horrors.”

After returning to the U.S., he continued to visit Europe, working with Eduoard Manet and James McNeill Whistler (whom he called a “first-class specimen of an eccentric man”). He exhibited in Paris and elsewhere, including New York where he taught at the Art Students League and Cooper Union, did portrait commissions, and had his home.

In 1882 an art collector saw a painting that Weir had just bought for $560 (about $16,000 today). He wanted the work and offered Weir $10 cash and an old farmhouse at Nod Hill Road and Pelham Lane, along with 152 acres in Wilton and Ridgefield, for the painting. Weir loved the farm’s rolling meadows, rock outcroppings, stone walls, apple orchard, old barns, and farmhouse, built around 1780. The place would inspire many paintings and encourage his move to Impressionism. Weir often painted outdoors there, and invited friends to do the same, including Childe Hassam, Albert Pinkham Ryder, John Singer Sargent, and John Twachtman. Best known for his oils, Weir was also accomplished in watercolors, etching, and stained glass, creating not only landscapes, but portraits and figure studies. Today his works are in many top museums in America and Europe. By the 20th Century he had become a major figure in American art. A founder and president of the Society of American Artists, he also led the National Academy of Design and was on the board of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He died in 1919, but the farm remained a home of artists for decades. Best known was Mahonri Mackintosh Young, who in 1931 married Weir’s daughter, Dorothy.

In 1882 an art collector saw a painting that Weir had just bought for $560 (about $16,000 today). He wanted the work and offered Weir $10 cash and an old farmhouse at Nod Hill Road and Pelham Lane, along with 152 acres in Wilton and Ridgefield, for the painting. Weir loved the farm’s rolling meadows, rock outcroppings, stone walls, apple orchard, old barns, and farmhouse, built around 1780. The place would inspire many paintings and encourage his move to Impressionism. Weir often painted outdoors there, and invited friends to do the same, including Childe Hassam, Albert Pinkham Ryder, John Singer Sargent, and John Twachtman. Best known for his oils, Weir was also accomplished in watercolors, etching, and stained glass, creating not only landscapes, but portraits and figure studies. Today his works are in many top museums in America and Europe. By the 20th Century he had become a major figure in American art. A founder and president of the Society of American Artists, he also led the National Academy of Design and was on the board of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He died in 1919, but the farm remained a home of artists for decades. Best known was Mahonri Mackintosh Young, who in 1931 married Weir’s daughter, Dorothy.

Twenty days after his birth in 1877 in Salt Lake City, Young was blessed by his grandfather, head of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and governor of Utah territory. Brigham Young had led the Mormons west in search of their promised land. Exhausted and ill as their wagon train approached what was to become Salt Lake City, he looked down at a valley and said, “This is the place.” A century later, grandson Mahonri engraved those words atop his massive “This Is the Place Monument” outside Salt Lake City.

Mahonri Young grew up in Salt Lake City, studied art there, and became an illustrator for a local newspaper. By 1899 he had enrolled in the Art Students League in New York, where he later taught.

In 1901 Young began his studies in Europe where he met many artists and writers — Ernest Hemingway was a fan of his work. He gained international recognition when his paintings were exhibited at the Salon, the official exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

However, Young still loved his native West. Many of his paintings, etchings and sculptures dealt with Native Americans, cowboys, horses, and other aspects of Western life. He also drew and painted industrial workers, even prizefighters.

Although Young had visited the farm early in the century, Dorothy’s father wasn’t a catalyst in his marriage. “No matter how friendly Weir always was to us … younger artists, he never introduced us to any of his three charming daughters,” Young said. “We never met any of them until after he died. But it was no use. I married the most beautiful, the finest, the most talented of them, Dorothy.” Dorothy was, indeed, talented; she had studied at the National Academy of Design and was a member of the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors. Many of her paintings are now at Brigham Young University’s Museum of Art.

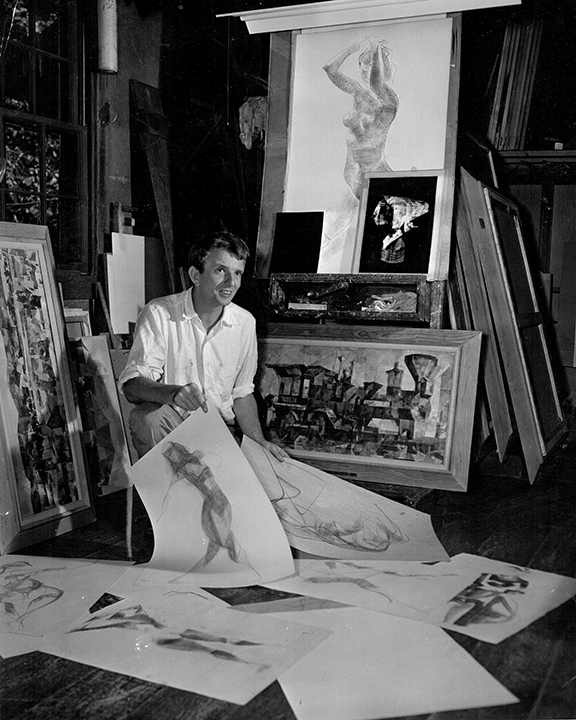

In 1932 Young moved to the farm, creating hundreds of sketches and paintings of life there, including scenes depicting animals, crops and farm laborers. He also built a studio, roomy and well-lighted enough to handle sizable sculptures. In 1939, he received a $39,000 commission ($789,000 today) to produce the 60-foot-high monument to his grandfather, unveiled eight years later. Most of the work was done in Ridgefield; the statues were shipped by rail to Utah.

In 1950, Young created the sculpture representing Utah in the National Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol in Washington — a rendering of his grandfather. His works are in the collections of many major museums, including the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

In 1950, Young created the sculpture representing Utah in the National Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol in Washington — a rendering of his grandfather. His works are in the collections of many major museums, including the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

In 1952, a young Ridgefield artist knocked on Young’s door and introduced himself. Sperry Andrews and his wife Doris had just seen a Weir exhibit in New York whose catalogue introduction was written by Young. Sperry wanted to meet the venerable artist who lived only a mile and a half away. He, Doris, and Mahonri soon became close friends. When Young died in 1957, 10 years after Dorothy, the Andrewses bought his farm.

Andrews, whose ancestors had hailed from Danbury, was born in 1917 in Manhattan and began sketching seriously at 8. He studied at the National Academy of Design and Art Students League, where he met fellow artist Doris Bass, a Kentuckian who became his wife for 55 years. Andrews was a respected artist whose specialty was plein air landscapes — his mobile studio was a Willys Jeep with all but the driver’s seat removed. Times art critic Vivien Raynor said he “paints the Connecticut countryside, but with considerably more panache than Weir… Though he uses richer color and seldom if ever includes figures, Mr. Andrews often recalls painter Fairfield Porter in the suppleness of his Impressionistic brushwork…”Andrews worked in oils, watercolors, charcoal, and pencil, and over his long life, produced more than 10,000 works, some now in major collections and museums.

In the late 1970’s, with development encroaching on the farm, the Andrewses began a grassroots effort to preserve the old farm for future generations of art lovers and artists. The Nature Conservancy, Trust for Public Land, and State of Connecticut, joined in, as did politicians. Finally in 1990, Congress created Weir Farm National Historic Site, the only national park property to celebrate American painting.

Sperry Andrews was 87 when he died in 2005, two years after Doris. Doris Andrews was, according to daughter Catherine, “a brilliant watercolorist. She really gave up her artwork for him, when they got married and started a family.”

Catherine recalled once when her father and several artist friends were sitting around and her brother, Sperry, pulled out some of Doris’s early watercolors.

“Everyone present was just amazed at how beautiful they were,” Catherine said. “There was just this stunned silence.”

Then her father blurted out, ‘Oh, my God, I should have given up my life

for hers.’ ”

Today, Weir Farm continues to nurture artists through its artist-in-residence program, picking ten artists a year to live and work at the former home of the Weirs, Youngs and Andrewses. More than 200 artists from the U.S., Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia have participated over the years.

Works by the five artists mentioned here, as well as others connected with the farm, can be seen at the park’s Burlingham House Welcome Center, 735 Nod Hill Road, Wilton, open Wednesday to Sunday, 10 to 4. The grounds are open daily during daylight hours, allowing everyone to see scenery that inspired great artists. •