On a summer’s evening, children romp in the playground, families gather for a CHIRP concert, and seniors take leisurely strolls on one of Ridgefield’s most historic pieces of land. Treasured today as a place of recreation and relaxation, Ballard Park has for centuries been a home of noteworthy people who’ve contributed to not only the town but also the nation.

In 1708, Ridgefield’s first landowners, called “proprietors,” designed their village, laying out a “Town Street” and 25 home lots along the middle of three ridges. On the west side of what’s now called Main Street, lots stretched from Wilton Road West to Catoonah Street; on the east, from the Ye Burying Yard at Wilton Road East to around Prospect Street. Land north of these lots was left for future pioneers. On the west side, Benjamin Burt, the first blacksmith, got the lot on the north side of today’s Catoonah Street as a bonus for moving here. Daniel Sherwood was wooed to be the town’s first miller with the next lot — where CVS is today.

A postcard, lithographed in Germany, showing the Biglow mansion around 1910. The historic building was razed in 1964 by request of Elizabeth Biglow Ballard, its last owner.

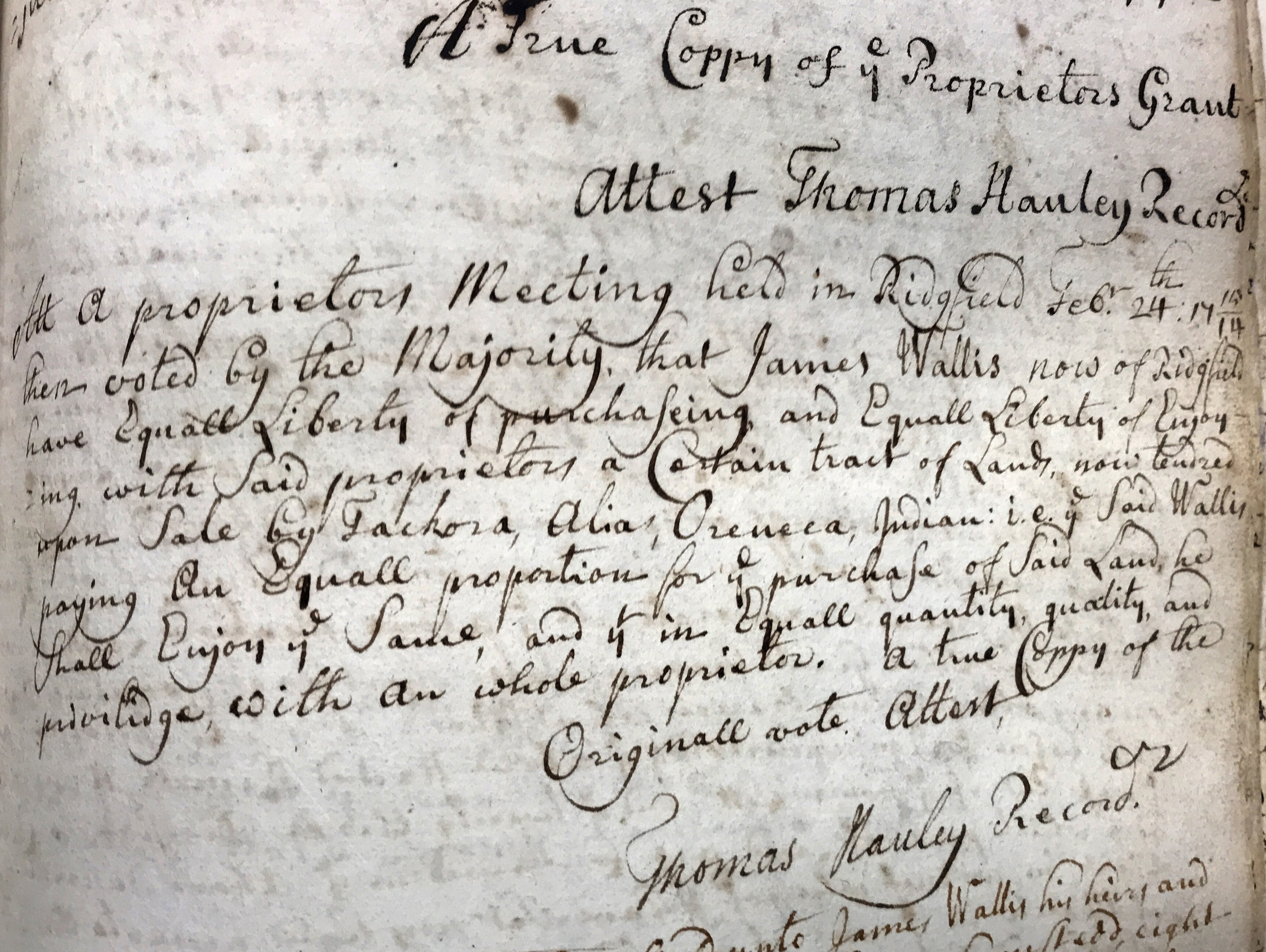

The Rev. Thomas Hauley, the register or town clerk, recorded this 1715 proprietors grant to James Wallis, allowing him to join with the town’s proprietors in buying a huge tract of land northwesterly of Lake Mamanasco from “Tackora, alias Oreneca, Indian.” Wallis (Wallace) later moved to this territory, some of which became part of North Salem, N.Y.

The Sad Sailor: James Wallace

Then came a man with no special talents, except perhaps charm and gumption. Born about 1675 in Scotland, James Wallis (later Wallace) was a young man working on the docks of Glasgow when he was “shanghaied” by the Royal Navy and pressed into service. He spent several unhappy years as a sailor. One night around 1705, when his ship was anchored off Norwalk, he slid down a rope into Long Island Sound and swam to the shore.

He liked what he found, and Norwalk liked him. Within a year, the personable Wallis had won the heart and hand of Mary Hyatt, 24-year-old daughter of leading citizens Thomas and Mary Saint John Hyatt. His father-in-law soon became one of the 25 who purchased 20,000 acres of native lands north of Norwalk and began settling Ridgefield. By 1715 Wallis had earned enough to join the proprietors in the purchase of more land from the Native Americans, northwesterly of Lake Mamanasco. Two years later, he bought and built a home on the Town Street lot just north of Sherwood’s that would become Ballard Park.

Wallace and at least two sons eventually moved to the remote territory northwest of Mamanasco. However, in 1730, when the colony line was moved, his farm wound up in North Salem, N.Y., where Wallace Road today recalls his family’s role in that town’s history. James died there in 1764, but both he and Mary are buried in Ridgefield’s ancient Titicus Cemetery. Several of their grandchildren fought in the Revolution, seeking freedom from British domination — just as James had in sliding down a warship rope three quarters of a century earlier.

The Rev. Thomas Hauley, the register or town clerk, recorded this 1715 proprietors grant to James Wallis, allowing him to join with the town’s proprietors in buying a huge tract of land northwesterly of Lake Mamanasco from “Tackora, alias Oreneca, Indian.” Wallis (Wallace) later moved to this territory, some of which became part of North Salem, N.Y.

The Rev. Thomas Hauley, the register or town clerk, recorded this 1715 proprietors grant to James Wallis, allowing him to join with the town’s proprietors in buying a huge tract of land northwesterly of Lake Mamanasco from “Tackora, alias Oreneca, Indian.” Wallis (Wallace) later moved to this territory, some of which became part of North Salem, N.Y.The Proud Soldier: Philip Burr Bradley

In 1764, Philip Burr Bradley of Fairfield bought the old Wallace homestead on Main Street, now 13 acres. A first cousin of Vice President Aaron Burr, Bradley got his feet wet in civic service as a selectman and colony representative before the war but after hostilities broke out, he became one of Connecticut’s leading soldiers, named commander of the Fifth Connecticut Regiment. Col. Bradley saw much combat, wintered at Valley Forge, and worked closely with General Washington. Miraculously, his own homestead escaped burning by the British during the nearby Battle of Ridgefield in April of 1777.

After the war Bradley served in the legislature during a critical period when the new “State of Connecticut” was being organized and its young government was struggling with heavy war debts. President Washington named him Connecticut’s first “marshal” — the top federal law enforcement official in the state.

Bradley was also a businessman and landowner with interests in local mills and a tannery. As perhaps the wealthiest man in town, he undoubtedly spruced up his Main Street homestead to meet the standards of the time. There have been undocumented reports that George Washington visited him there at least once.

While Bradley died in 1827, his family held on to the homestead until mid-century. In 1862, a recently retired New York City physician named Dr. Daniel Adams bought the place, continuing the home’s legacy.

The Father of Modern Baseball:

Dr. Daniel Adams

Doc Adams wasn’t your ordinary physician. In the city he had played with and been president of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club. In 1857, as head of the Rules Committee for the National Association of Base Ball Players, he composed “Laws of Base Ball.” Nearly 150 years later, those few hand-written sheets setting down the basics of today’s baseball sold at auction for a record-breaking $3.3 million, adding evidence to the belief that Doc Adams was the man behind the modern-day game. “He’s the true father of baseball and you’ve never heard of him,” said a baseball historian and a consultant on the sale. Efforts have been underway for years to get Doc Adams added to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

In Ridgefield, Adams left both baseball and medicine behind. He was a founder and first president of the Ridgefield Savings Bank (today’s Fairfield County Bank) and first president of the Ridgefield Library and made many other contributions to the community before moving in 1885 to New Haven, home of alma mater Yale. He died there in 1899.

Songs for the Soul: Lucius Horatio Biglow

Finally, in 1887 came Lucius Horatio Biglow and his family. His Biglow and Main was one of the nation’s earliest and largest sacred music publishers, distributing the work of such renowned hymn writers as Fanny Crosby, William B. Bradbury, Robert Lowry, Ira D. Sankey, William Howard Doane, and Philip P. Bliss.

The “Main” was Ridgefield native Sylvester Main, a music teacher and hymn composer who also no doubt sang the town’s praises to his partner. Sylvester’s son, Hubert, wrote music for many of the songs Biglow published. Both Mains were close friends of Fanny Crosby, the prolific blind hymnist who spent her childhood on lower Main Street.

Biglow called his estate Graeloe, coined from the name of his wife, Anna Graham, and his own, with the E’s added for a Gaelic flavor. Among his contributions locally was the half-timbered, Tudoresque building that today houses Planet Pizza and other village businesses.

After he died in 1909, daughter Elizabeth and her husband, Edward Ballard, made Graeloe their summer and weekend home. Elizabeth was a founder of the Ridgefield Boys and Girls Club, and a pillar of the Ridgefield Garden Club. When Elizabeth died in 1964 at age 87, she ordered that her house be demolished, believing the village needed a real park rather than an old, white elephant to burden to the taxpayers.

However, several outbuildings were retained, including her greenhouse, now used by the local garden clubs. Ridgefield Garden Club members have revamped gardens and other features of the five-acre park. Just recently they restored a wrought-iron pergola, designed in 1930 by noted landscape architect Fletcher Steele and relocated from the Westmoreland estate

in 1992.

After the Ridgefield Press wrote an editorial suggesting that there be a place in Ballard Park for concerts, the Ridgefield Woman’s Club took up the cause, raised $6,000, and built this bandstand in 1975.

The park has been a setting for not only history, but a 1999 Hollywood movie. “Spring Forward,” written and directed by Ridgefield High School graduate Tom Gilroy, stars Ned Beatty and Liev Schrieber, and tells the story of two park workers. One plotline involves the discovery of a homeless man living under the bandstand — something that really happened in Ballard Park around 1980.

In the months to come, the park will be closely inspected by the National Park Service, seeking relics of the Battle of Ridgefield. Doc Adams had already uncovered two cannonballs on the property 150 years earlier. Such is the varied and rich heritage of Ballard Park — a sad sailor, a proud soldier, a doctor who wielded an early bat, a man who sold songs for the soul, and his daughter who cherished Ridgefield. •