Take one step into the home of former professional dancer Walter Schalk and you can feel the beat. And why not. Nearly 160,000 pairs of feet have pounded their way over the studio floors. Sixty-two years of shows have been choreographed, costumed, and archived; most of them right there in the Wilton home where the talented performer built The Walter Schalk School of Dance into a thriving business—one step at a time.

Schalk began his dance career at nine years-old by swinging to ballroom tunes under the direction of a World War II vet whose own performing aspirations were cut short by an injury. Under his instructor’s tutelage, Walter and his fellow dancers became a formidable dance troupe and was invited to perform on national television on a regular basis. His highlights include The Ed Sullivan Show, The Fred Waring Show, performing with Frank Sinatra and becoming a finalist at the Harvest Moon Ball, a famous amateur dance contest.

Talent aside, Schalk considered dancing a hobby and maybe a way to woo the women with his moves. His advertising career in letterpress printing was in full throttle when America’s military intervention in Korea led him to serve. Born of hardworking German immigrants it was ironic that he spent his service in Europe playing soccer on the US Infantry’s German American Friendship Team, a public relations effort promoting reconciliation after World War II.

At clubs Schalk remained the envy of his buddies because back then, a good dancer was one of the most popular guys in the room and had his pick of partners. It wasn’t long before friends asked him to teach them to dance. That was followed by wives and soon after his friends’ children. As ballroom morphed into jazz, swing, disco, show tunes and beyond, Schalk changed with the times. By 2019, when the final curtain closed, The Walter Schalk Dance Studio had become a household name throughout Fairfield County.

“I started in the house next door and was there for over twenty years,” says the gregarious 89-year-old who hopes to chronicle his fascinating story in a memoir. “I asked my neighbor for the right of first refusal if he ever sold his property.”

It took his neighbor twenty-five years to honor the deal. All that Schalk had to do was match an existing offer and the eight-acre parcel would be his. The stipulation—he had to give his answer immediately.

“I said, give me at least a half hour,” recalls Schalk who then immediately got on the phone scrambling to work out the financing.

It was Schalk’s love of boating and fishing that steered him toward his home design. Intrigued by a house that he often passed set on a bluff overlooking the Connecticut River, he began taking pictures and sketching, imagining how it might sit on the gently sloping property. Every room would look out at the pastural view including a lower walk out level.

If his architect thought the request to build the exterior shell without laying out an interior floorplan was unusual, he remained unphased. Once completed, Schalk had very specific ideas on how the inside would look.

“I wanted to walk in the front door and see everything,” he says.

The entry of the home is immediately met with the dramatic view from a palladian window in the step-down living room. Off the entry is the study where Schalk works amidst piles of photographs and show memorabilia. The beautiful paneling and built-ins were done by a very talented artisan who didn’t have time to expand his skill to the rest of the house. Schalk’s solution was to do it himself. He matched the woodwork in the adjacent master suite and from there created much of the remaining visually pleasing finishing work.

One of the remarkable features about the floorplan is how the kitchen, dining room and living room float together as one. Schalk admits that the open floor plan wasn’t as popular 36 years ago but adds that “it’s a good party house” sometimes holding 200 guests.

The interior, intended as a four bedroom, was choreographed to embrace the dance school needs. A sound/video studio is loaded with equipment, much now obsolete. Videos of all the performances put on over the six decades are crammed onto shelves. Another room is where costume design took place.

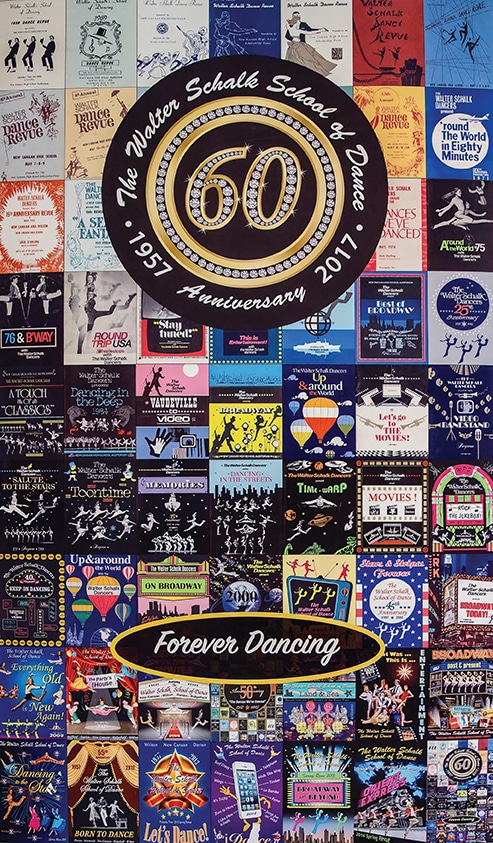

A wide-open staircase that could act as a stage itself curves down into a large, mirrored studio—the space, currently overwhelmed with remnants of the successful school. It took Schalk, his cousin and her husband a month to organize the countless photographs and playbooks into piles laid out by years and towns where they were presented.

Though a little overwhelmed by the memorabilia he is trying to organize, Schalk is immensely proud of his home which he loves in all seasons especially at Christmas. The man who made a living entertaining still keeps folks swooning during the holidays with Wally’s World, a festival of thousands of lights named for his late beloved dog. Anyone who has driven by the home on Drum Hill Road during the holidays will testify to how spectacular the annual display truly is.

While Schalk misses his dance school, he has no trouble staying busy. He jokingly says that he is already living in his nursing home. His one and only regret; “life for me is going by just so fast.” •